Metabolism of 2024 FDA Approved Small Molecules – PART 2

By Julia Shanu-Wilson

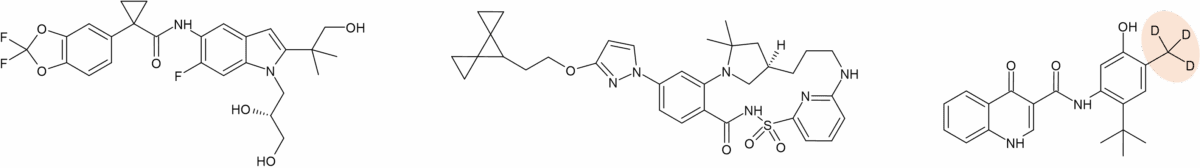

As we near the end of 2025, we return to look at other interesting aspects of metabolism of last year’s FDA-approved drugs [1]. First, we take a look at a couple of drugs developed by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries (deuruxolitinib) and Vertex (deutivacaftor) where deuterium was incorporated in order to manage metabolism and lengthen half-life.

Managing metabolism by incorporation of deuterium

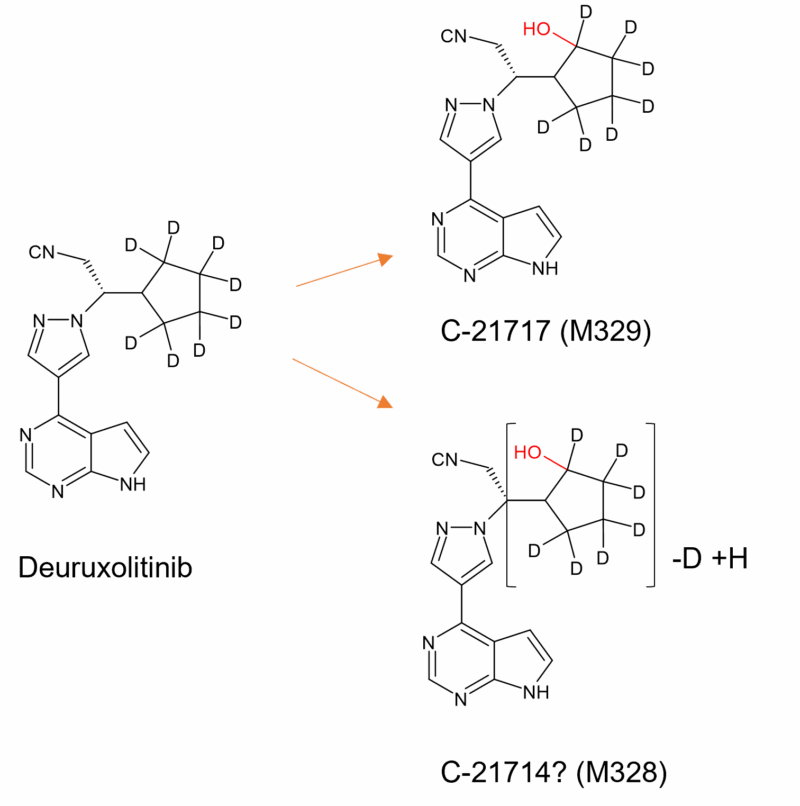

Figure 1: Main plasma metabolites of deuruxolitinib adapted from Figure 3 on p72 in [4]. Hydroxylation of the cyclopentyl ring still occurs (M329) and interestingly also loss of deuterium in M328. Oxidation in other moieties also occurs but to a lesser extent (metabolite structures not shown).

Deuruxolitinib (Leqselvi®) was approved to treat severe alopecia areata and is a “deuterium clone” of the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib, already on the market for treatment of multiple conditions such as polycythemia vera, myelofibrosis, chronic graft-versus-host disease, acute graft-versus-host disease, atopic dermatitis and vitiligo.

Ruxolitinib is extensively metabolised to multiple oxidised metabolites, mainly by CYP3A4 and to a lesser extent by CYP2C9. The major circulating metabolites in humans are formed by 2-hydroxylation of the cyclopentyl ring (M18), and two stereoisomers formed by 3-hydroxylation of the cyclopentyl ring (M16 and M27). Active metabolites contribute 18% of the overall pharmacodynamics of ruxolitinib [2]. Previously microbial biotransformation was used to make all the diastereoisomers of the 2- and 3- hydroxylated metabolites of ruxolitinib, in addition to the ketone derivatives [3].

In order to reduce metabolism at the metabolically vulnerable cyclopentyl ring, deuterium was extensively incorporated in this moeity, resulting in a longer half life. Despite this, deuruxolitinib is still extensively biotransformed through mono and di oxidations and subsequent glucuronidation. The two most abundant circulating metabolites in humans are C-21714 and C-21717 (Figure 1) which comprise 6% and 5% of total drug exposure, respectively. However there was no metabolite above the 10% threshold and no unique human metabolites are formed [4].

Whilst the full biotransformation pathway of deuruxolitinib and the structures of the main metabolites have not been published, a proposed scheme is included in the NDA submission document [4].

Interestingly the two main cytochrome P450s involved in its metabolism, CYP2C9 and CYP3A4, have switched in dominance compared to ruxolitinib. Since deuruxolitinib is metabolised mainly by CYP2C9 (76%) rather than CYP3A4 (21%), and the gene encoding CYP2C9 has polymorphisms that impact metabolic function, assessment of PK in the population with the relevant genotypes was listed as a postmarketing requirement [4]. Prospective recipients of the drug are required to take a CYP2C9 genotyping test as the drug is not recommended for individuals who are poor metabolisers.

The other deuterated drug in this set is one of three components that make up the cystic fibrosis drug Alyftrek®. In addition to tezacaftor and vanzacaftor, a deuterated form of ivacaftor called deutivacaftor forms the third component (Figure 2). Whilst information on the metabolism of vanzacaftor is not publicly available, other than it is extensively metabolised by CYP3A4/5 and with no major circulating metabolites [5], biotransformation details of tezacaftor and ivacaftor have previously been published.

Figure 2a: Structures of tezacaftor, vanzacaftor and deutivacaftor that make up Alyftrek®

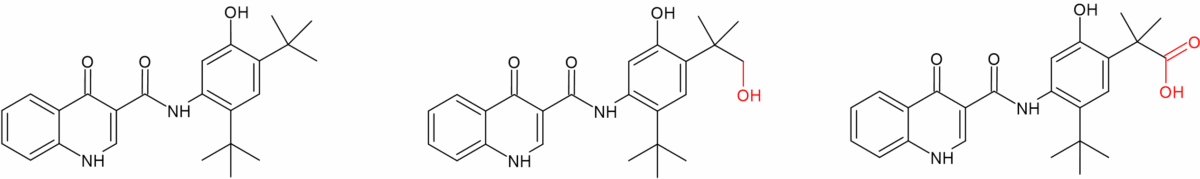

Three major metabolites of tezacaftor circulate in humans (M1-TEZ, M2-TEZ and M5-TEZ) of which M1-TEZ is considered as pharmacologically active as the parent. Deutivacaftor’s predecessor ivacaftor also has a major active metabolite (M1-IVA), however it has only one sixth the potency of the parent. The other major metabolite of ivacaftor (M6-IVA) is pharmacologically inactive [6].

Figure 2b: Ivacaftor and its major metabolites M1 (active) and M6 (inactive)

Like deuruxolitinib, deutivacaftor was originally made by Concert Pharmaceuticals. Two options were evaluated at the time – a d9 and d18 form of ivacaftor, however it was the d9 version CTP-656 that was taken forward, and subsequently acquired by Vertex. CTP-656 was reported to exhibit remarkable metabolic stability in-vitro compared to ivacaftor, and the longer in vivo half-life indicated a once-daily dose regimen was viable instead of twice-daily dosing [7]. Like the non-deuterated original, deutivacaftor is primarily metabolised by CYP3A4/5 to form two major circulating metabolites, M1-D-IVA and M6-D-IVA. Presumably the position of oxidation of deutivacaftor (also termed D-IVA) to M1-D-IVA and M6-D-IVA mirror ivacaftor’s M1 and M6. M1-D-IVA has approximately one-fifth the potency of deutivacaftor and is pharmacologically active. M6-D-IVA is not considered pharmacologically active [5].

Further involvement of CYP2C9 as a route to metabolism

Another drug metabolised primarily by CYP2C9 is the primary biliary cholangitis drug seladelpar (Livdelzi®). Metabolism results in 3 inactive major metabolites, seladelpar sulfoxide M1, desethyl-seladelpar M2, and desethyl-seladelpar sulfoxide M3 (Figure 3). CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 are also involved but to a lesser extent [12]. Since seladelpar is a CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 substrate, increased seladelpar AUC is expected in patients who are CYP2C9 poor metabolisers with concomitant use of a moderate to strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, and thus close monitoring is indicated.

Figure 3: Main CYP2C9 metabolites of seladelpar

Involvement of aldehyde oxidase

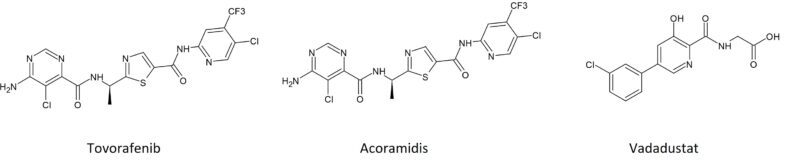

Tovorafenib (Ojemda®) was approved to treat paediatric low-grade glioma harbouring an activating RAF alteration. Although the parent drug is the most abundant component in plasma, several metabolites form in-vivo through oxidation and, to a lesser extent, by amide hydrolysis. As well as oxidation by CYP2C8, tovorafenib is also subject to metabolism by aldehyde oxidase [8]. Of the plasma metabolites, the most abundant reported were oxidised metabolites M3 and M26 and a secondary glucuronide M16. None reached > 10% of total plasma radioactivity exposure.

Although the structures of these metabolites have not been published, the presence of an electron-deficient sp2 carbon adjacent to a heterocyclic nitrogen makes the involvement of AO unsurprising. Based on in vitro phenotyping study data and biotransformation pathway information determined from the human AME study, the contribution of CYP2C8 and aldehyde oxidase accounts for 49% and 23% of the metabolism, respectively.

Conjugated metabolites

Phase II metabolic routes feature in the metabolism of a number of the approved drugs, including acoramidis, vadadustat and inavolisib.

Acoramidis (Attruby®) was approved to treat cardiomyopathy of transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis and is primarily metabolised via UGTs 1A9, 1A1 and 2B7 to an acyl glucuronide, which comprises 8% of total circulating radioactivity. Interestingly the acyl glucuronide is active, being one third pharmacologically active as the parent drug. However, it is stated to possess only a low potential for covalent binding and does not contribute to pharmacological activity in-vivo [9].

Glucuronidation is also the main route of metabolism of vadadustat (Vafseo®), which was approved for treatment of symptomatic anaemia associated with chronic kidney disease. Predominantly UGT1A9 is involved in formation of a major O-glucuronide, which comprises 15% of the plasma radioactive AUC. The O-glucuronide is 200-fold less potent than the parent drug and inhibits recombinant human PHD2 at only micromolar concentration [11]. In contrast to acoramidis, although acyl glucuronidation is observed, it is only a minor route of metabolism of vadadustat (< 0.1% plasma radioactivity) [10].

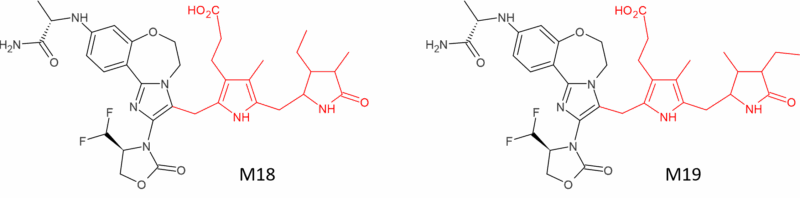

Rather more unusual are conjugated metabolites of the targeted breast cancer drug inavolisib (Itovebi®). Inavolisib is mainly metabolised by hydrolysis but scientists at Genentech noticed the presence of two unusual conjugates in faeces comprising 4.2% of the dose in the human radiolabelled mass balance study. Further investigation revealed M18 and M19 to be formed from conjugation of inavolisib to one half each of a stercobilin molecule in the gut [13] (Figure 4). It’s worth highlighting that although stercobilin-derived drug metabolites have not been reported previously, the authors of [13] highlight the possibility that other drugs with electron-rich imidazoles or similar ring systems could undergo reactions with stercobilin.

Figure 4: Part stercobilin conjugates of inavolisib formed in faeces

The atypical and unexpected

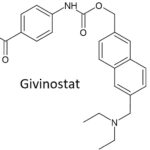

There are a couple of other drugs in this group with atypical or unexpected routes of metabolism. The Duchenne muscular dystrophy drug givinostat (Duvyzat®) is extensively metabolised, but not through routes involving CYPs or UGTs. Four major metabolites have been characterised in humans and preclinical species which are all pharmacologically inactive. One metabolite in particular, a naphtalenic fragment formed by oxidative cleavage of the carbamic bond (ITF2440), had the highest metabolite to parent ratio in human plasma but mystifyingly not a specific enzyme was identified as responsible. Other metabolites were shown to be formed through involvement of human mitochondrial amidoxime reducing components (mARCs 1 and 2), which reduce the hydroxamic acid to an amide (ITF2374). However, hydrolysis of the hydroxamic acid to form a carboxylic acid metabolite (ITF2375) occurs mainly in the blood but does not involve either carboxylesterases CES1 or CES2 [14].

There are a couple of other drugs in this group with atypical or unexpected routes of metabolism. The Duchenne muscular dystrophy drug givinostat (Duvyzat®) is extensively metabolised, but not through routes involving CYPs or UGTs. Four major metabolites have been characterised in humans and preclinical species which are all pharmacologically inactive. One metabolite in particular, a naphtalenic fragment formed by oxidative cleavage of the carbamic bond (ITF2440), had the highest metabolite to parent ratio in human plasma but mystifyingly not a specific enzyme was identified as responsible. Other metabolites were shown to be formed through involvement of human mitochondrial amidoxime reducing components (mARCs 1 and 2), which reduce the hydroxamic acid to an amide (ITF2374). However, hydrolysis of the hydroxamic acid to form a carboxylic acid metabolite (ITF2375) occurs mainly in the blood but does not involve either carboxylesterases CES1 or CES2 [14].

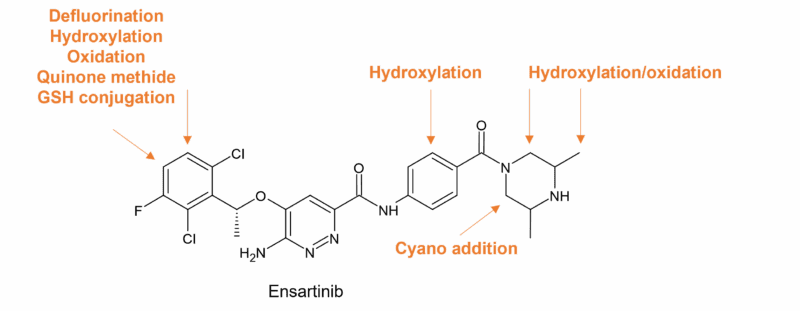

Metabolism of ensartib (Ensacove®), approved to treat NSCLC, is interesting due to a bioactivation mechanism observed in-vitro, which is proposed to occur through “unexpected metabolic pathways” to generate reactive intermediates [15]. Four oxidised metabolites as well as GSH and cyanide conjugates were characterised in HLMs. The piperazine ring was bioactivated through generation of intermediate iminium ions following hydroxylation and subsequent loss of water, while the dichloro-phenyl group was bioactivated through oxidative defluorination generating a quinone methide intermediate. The authors of [15] suggest that modifying the piperazine ring or an isosteric replacement could block the initial hydroxylation reaction that leads to the formation of some reactive metabolites observed in-vitro.

Figure 5: Ensartinib sites of metabolism in HLMs (taken from Figure 9 in [15])

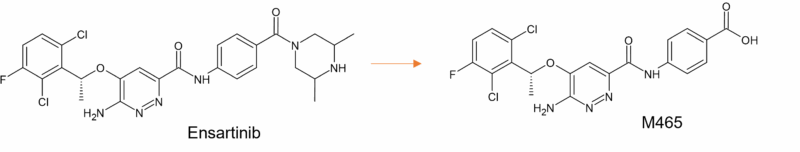

Despite extensive metabolism, the human mass balance study reports only one major circulating metabolite of ensartinib (M465), at 28% of the plasma total radioactivity (Figure 6). Other circulating metabolites were minor, accounting for less than 10% [16]. Metabolism is primarily mediated by CYP3A4/5 [17].

Figure 6: Main circulating metabolite of ensartinib in humans

This concludes our look-see at metabolism of some of the small molecule drugs approved last year by the FDA.

Note that where Hypha may have been involved in any of the projects described, no details on metabolites other than what is publicly available have been disclosed in this article.

References

[1] FDA New Drug Therapy Approvals 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/novel-drug-approvals-fda/novel-drug-approvals-2024

[2] Metabolism, excretion, and pharmacokinetics of [14C]INCB018424, a selective Janus tyrosine kinase 1/2 inhibitor, in humans. Shilling et al. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010; 38(11): 2023-2031. doi:10.1124/dmd.110.033787.

[3] Routes for Synthesis of Metabolites of Ruxolitinib and Epacadostat. Evans et al. Poster presented at Drug Discovery Chemistry 2022. https://www.hyphadiscovery.com/poster/routes-for-synthesis-of-metabolites-of-ruxolitinib-and-epacadostat/

[4] https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/217900Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf

[5] https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/alyftrek-epar-product-information_en.pdf

[6] https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9634/smpc#gref

[7] Altering Metabolic Profiles of Drugs by Precision Deuteration 2: Discovery of a Deuterated Analog of Ivacaftor with Differentiated Pharmacokinetics for Clinical Development. Harbeson et al. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017, 362(2): 359-367. doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.241497

[9] https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/216540s000lbl.pdf

[10] https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/215192s000lbl.pdf

[11] https://ir.akebia.com/static-files/37e983c4-a5e9-4af9-afa5-3cf3fae34b30

[12] https://www.gilead.com/-/media/files/pdfs/medicines/pbc/livdelzi/livdelzi_pi.pdf

[13] Discovery of Unprecedented Human Stercobilin Conjugates. Cho et al. Drug Metab Dispos. 2024; 52(9): 981-987. doi:10.1124/dmd.124.001725

[14] https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2024/217865Orig1s000IntegratedR.pdf

[15] Characterization of Stable and Reactive Metabolites of the Anticancer Drug, Ensartinib, in Human Liver Microsomes Using LC-MS/MS: An in silico and Practical Bioactivation Approach. Abdelhameed et al. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2020, 14, 5259–5273. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S274018

[16] Mass balance, metabolic disposition, and pharmacokinetics of [14C]ensartinib, a novel potent anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor, in healthy subjects following oral administration. Zhou et al. Mass Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2020;86(6):719-730. doi:10.1007/s00280-020-04159-0.

[17] https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2025/218171Orig1s000IntegratedR.pdf